|

[August 25th 2005]

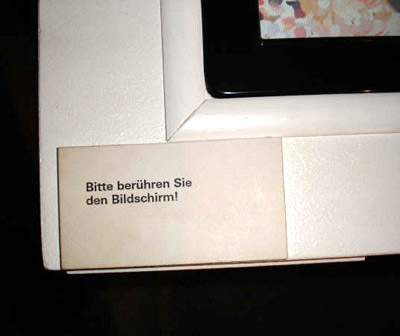

From The Algorithmic Revolution. Photo: Emil Bach Soerensen.

The Algorithmic Revolution

Please Touch the Screen!

'Usually, a revolution is about to happen and it announces itself with a 'roar'. The Algorithmic Revolution has already happened, and, despite remaining largely unnoticed, it has been all the more effective. There is, namely, no longer any area of our social and cultural life that is not penetrated by algorithms: Cameras, cars, planes, ships, household appliances, hospitals, banks, factories, shopping malls, traffic, architecture, literature, art, music. The Algorithmic Revolution began around 1930 in science, around 1960 in art.' (Peter Weibel, ZKM 2004).

The German Centre for Art and Media (ZKM) in Karlsruhe is currently showing the exhibition The Algorithmic Revolution which presents a historical outline of this radical change in the fine arts, music, design and architecture. The exhibition draws both on the ZKM collection and selected loans. It can be experienced until December 2005.

Two writers let themselves be inspired and give two different views on the exhibition in two separate articles. Emil Bach Soerensen visited the exhibition and gives a brief comment on two digital artworks to give us a reminder of the significance of the active human participant. Emil is finishing up his MA in visual culture and is

engaged in teaching, communication and discussion of issues related to design and cultural theory.

The above photo was taken at The Algorithmic Revolution, an exhibition at ZKM debating the major influence of algorithms on modern society and culture. I immediately fell in love with the message printed on this anonymous piece of cardboard because it conveys German pragmatism combined with a subtle sense of humour. We are normally told precisely how to behave in a museum space with things on display, so of course it makes sense to exchange the usual 'please don't touch' with the words, 'Bitte berühren Sie den Bildschirm' ('please touch the screen'), in an exhibition showing interactive art.

Casey Reas: Seoul_B (Fiume), 2004. Semi-automatic drawing machine. Courtesy of Bitforms Gallery. Image courtesy of ZKM. More Casey Reas: http://www.groupc.net

The text on this specific sign encourages the museum guests to touch a vertical screen facing the visitors in an installation with the software artworks, Seoul A and Seoul B, 2004, by Casey Reas. As a response to the touch of a finger, or a hand, highly coloured and complex patterns evolve and spread slowly over the surface of the screen. Some people lose interest after a few seconds others are involved for several minutes fascinated by the visuals generated by the meeting and exchange between human presence and digital algorithms.

From The Algorithmic Revolution. Photos: Emil Bach Soerensen.

Next to Casey Reas' work is another software installation Yellowtail, 1998-2000, by Golan Levin. Golan Levin relates to the same scene for digital art in New York as Casey Reas. Yellowtail is a good example of a piece where the art is created as a temporary audio-visual response to the physical interaction of the user. Like Seoul A and Seoul B, Yellowtail is also an aesthetic exploration of human-computer interaction. It literally consists of a blank screen until somebody moves the mouse. Depending on the intensity and rhythm of the movements of the mouse the screen is lit by structures of light which generate digital sounds. In one mode the visuals and sound slowly fade away when the user is inactive or leaves the installation. In the other mode the shapes are continuously replaced

by the actions of the user. Both Seoul A/Seoul B and Yellowtail are at ZKM courtesy of Bitforms Gallery in New York - one of the very few galleries in the world specialized in providing a platform for selling digital artworks.

Yellowtail, Golan Levin (1998-2000). Screendump and photo from The Algorithmic Revolution. Photo: Emil Bach Soerensen. More Golan Levin: http://www.flong.com.

Some museum guests might wonder how the visual structures that respond to touch and movement of the mouse are produced? What are the rules of the game? How does the back end of the code, the algorithms behind the screen, work? A certain segment of the visitors already know that the Seoul pieces are written in the programming language Processing that Reas launched recently together with Ben Fry as a result of research at MIT's The Aesthetic + Computation Group. Some might also be able to analyse from the visual front to back end of the code. Others are just fascinated by the digital mirror and don't care much about code.

If we have a look at the artworks from a slightly different perspective, these pieces tell us about the basic relationship between the human participant and the digital interface. As many other artworks at The Algorithmic Revolution, the art of Casey Reas and Golan Levin fundamentally combine aesthetic nuances with a concern about human-computer interaction. For me it is striking that the aesthetic exploration of bodily presence as well as human expression, perception and imagination is an essential concern for many of the exhibited installations. Digital art is often inseparable from its user.

From The Algorithmic Revolution. Photo: Emil Bach Soerensen.

It has always been an essential concern for artists to evaluate and experiment with the relationship between the artwork and the spectator. Since the Renaissance architects, sculptors and painters have been occupied by an artistic ambition to produce, or distort, the mental experience of 3D space. In terms of interactive digital art the productive meeting between the user and the artwork is intensified and very concrete. Often it is reasonable to say that there is no art before the involvement of the user. The performance that happens in the space between the human beings and the machines is the art in itself.

The Algorithmic Revolution profoundly demonstrates that this notion of art, has its roots in the avant-garde in the beginning of the 20 th century and certainly also in the experimental art movements of the 1960s such as kinetic art, Op Art and Fluxus. (You might have a look at Søren Pold's article, 'The Algorithmic Revolution - Heavy machinery and abstract art in a new context at ZKM', for a discussion of the historical foundation of digital art. http://www.artificial.dk/articles/heavy.htm).

Looking at our cardboard sign again, the message takes on a beckoning tone: 'PLEASE touch the screen'. If the user doesn't touch the screen, the artwork is never fully realized.

Seoul A/Seoul B and Yellowtail are not critical or analytical works as for example Jeffrey Shaw's The Legible City, 1988-1991, David Rokeby's The Giver of Names, 1991 and Perry Hoberman's Barcode Hotel, 1994, or other classical pieces of digital art exhibited at The Algorithmic Revolution. But these pieces provide fine nuances and aesthetic sensibility to the exploration of human-computer interaction. And they remind us of the fundamental fact that the presence and activity of human beings is an essential material for the creation of the digital art event.

More Casey Reas: http://reas.com

More Golan Levin: http://www.flong.com

More about ZKM: http://www.zkm.de

|

|

|